The tortured flight of Explorer 1

For something a little different (we're still in lockdown in Melbourne and I can't get out to a dark sky site), here's a story about spin stabilisation and how it doesn't always work.

This is when an object spins while in free-fall, rather than tumbling. Tumbling, as the name suggests, is when the object spins in more than one axis. During the Second World War, bomb makers had realised that bombs that tumbled through the atmosphere on their way to their targets did not detonate reliably. In the same way, artillery shells wandered off their targets when they tumbled.

Making these missiles spin through their flight stopped them from tumbling. Shells could be spun by rifling in gun barrels, and bombs had fins that caused their spin, as well as pointing them towards the ground.

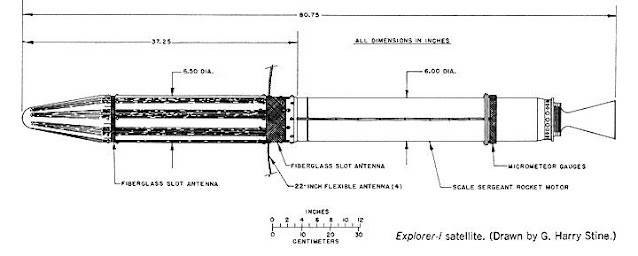

So in 1958, when the US launched their first satellite, Explorer 1, engineers decided to stabilise the final stage by spinning it along its long axis. Unlike Sputnik 1, Explorer 1 had a "rocket" shape. It was just over two metres long by just over 15 centimetres in diameter with an engine at the back.

But when the engineers spun their satellite, something odd happened. Rather than spinning like a javelin, the nose of the craft twisted outwards, and it ended up rotating "sideways", like a propeller. Data could still be received, but only when the satellite was pointed towards receivers on the ground.

Puzzled scientists eventually figured out that this behaviour was a result of the system moving to its lowest rotational kinetic energy state, where it rotates around its shortest axis. It was helped along its way by the flexibility of four whip antennas on the side of the craft dissipating the kinetic energy in the form of heat.

As a post script, Explorer 1 carried a Geiger counter. Observations from the mission led to the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts. The satellite remained in orbit for about 12 years, re-entering the atmosphere in March 1970.

Comments

Post a Comment