How I got some photos of some planets

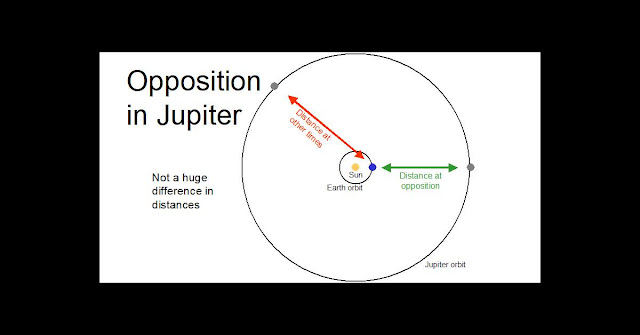

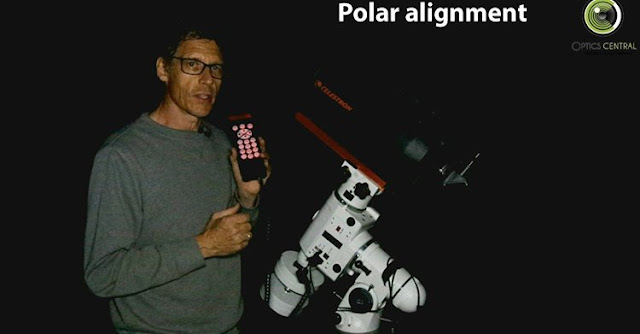

You can do this! I used inexpensive equipment to get some reasonable photos of Jupiter (and one of Saturn). In doing so, I learned a pile of lessons, which I've listed at the end. It's planetary season, with Jupiter just past opposition, meaning it's overhead at midnight. Saturn's not far behind. I'm a nebula hunter and not a planet expert, so I'm really a beginner in this area. Planets are tiny little things, but they're very bright. They're about as far, technically, as you can get from nebulas, which are large and dim. The aim We wanted to get some photos of planets to show what inexpensive equipment is reasonably capable of in the hands of someone who isn't much of an expert. I'm also keen on using non-premium equipment to take photos. I'm often quite pleased at the results you can get without having to shell out big bucks. The equipment For a scope, I grabbed a saxon 127 Maksutov on a go-to mount . I could have taken a similar...